|

|

- Search

| Asian J Kinesiol > Volume 20(4); 2018 > Article |

|

Abstract

OBJECTIVES

We aimed to evaluate physical activity patterns according to participation in the ‘sports for all’ programs in community-dwelling Korean adults. We also investigated the association between meeting physical activity guidelines and participation in sports activities and the risk of hypertension.

METHODS

For the present study, we clustered and randomly selected participants from Chungcheongbuk-do in Korea. From a total of 520 participants, 493 completed the survey, and the response rate was 92%. After excluding participants who had missing data for physical activity, demographics, health-related behaviors, and clinical health conditions, a total of 481 participants were included in the study.

RESULTS

We observed a lower risk of hypertension in the sports activities group than in the inactive group after adjustment for age and sex (OR: 0.42, 95% CI: 0.17-0.99). The results were unchanged after adjustment for education levels and household income. In the fully adjusted model, the ORs for hypertension were 0.36 (95% CI: 0.13-0.97) for the sports activity group and 0.33 (95% CI: 0.14-0.78) for those who met the physical activity guidelines.

CONCLUSIONS

The criterion of meeting the physical activity guidelines was significantly associated with a decreased risk of hypertension. In addition, participation in the sports for all program without meeting the recommended level of physical activity was independently associated with a lower risk of hypertension.

A wealth of evidence suggests that physical activity (PA) has substantial health benefits. These include the prevention of chronic diseases and disabilities as well as a reduced risk of mortality [1-3]. The International Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults recommends more than 150 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous PA per week [4]. Recently, the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare (KMHW) released new guidelines for PA for Korean adults [5]. Many previous studies have reported that meeting the guidelines for PA is associated with a decreased risk of metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, some forms of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and premature death [3,6-9]. However, despite the fact that a minimal amount of PA can yield many health benefits, most Koreans still do not meet the PA guidelines [10].

Hypertension is one of the most prevalent chronic diseases in Korea. The prevalence of hypertension in Korean adults was 29.1% in 2016, which represents a 5% increase from 24.5% in 2007 and is much higher than that of other chronic diseases. In addition, the WHO global health risks report listed hypertension as the primary cause of mortality among the 19 leading risk factors. Therefore, prevention and effective management of hypertension are important public health challenges. Epidemiological studies have reported that higher levels of PA are associated with reduced risk of hypertension in older adults [11,12]. Moreover, Kim et al. reported that increased PA reduced the systolic and diastolic blood pressure in overweight individuals with metabolic syndrome risk factors [13].

In addition to PA, participation in sports is increasing during leisure-time activity among the Korean population. In order to improve the health of the people at the national level, the government is promoting policies designed to encourage participation in sports activities. This effort focuses on emphasizing a core theme of “sport for all, play for life” through encouraging population of all ages, genders, and backgrounds to participate in sports. Leisure-time physical activities may contribute to reduced rates of chronic diseases and mortality [9,14,15]. However, there is limited research about the PA patterns of participants in sports activities during leisure time or the health benefits of participation in sports for all. Therefore, in the current study our goal was to evaluate PA patterns according to participation in the ‘sports for all’ programs in community-dwelling Korean adults. We also investigated the association between meeting PA guidelines and participating sports activities and the risk of hypertension.

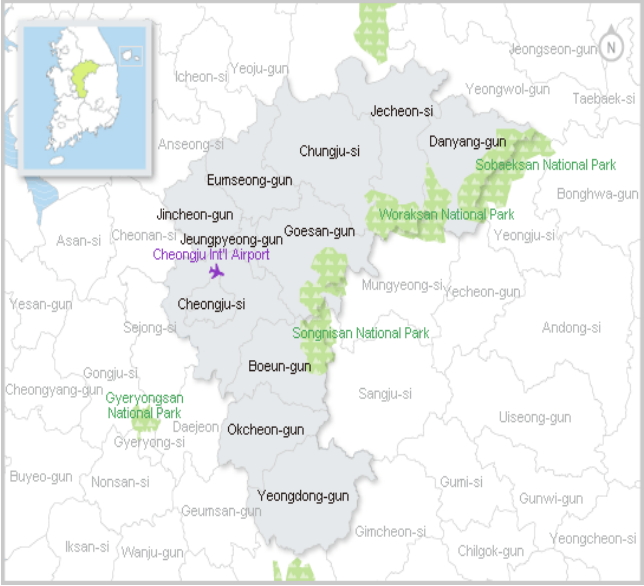

For the present study, we clustered and randomly selected the participants from Chungcheongbuk-do in Korea. Chungcheongbuk-do is uniquely landlocked in the center of South Korea (Figure 1). In 2017, it had an estimated population of 1,605 thousand and a population density of 217 people/km²; the total area is 7,407 km². We selected the target study population by matching the distribution of the population to that of the whole city, considering age and sex as the matching variables. We conducted a survey using a questionnaire on PA and sports activities, health-related behaviors, and morbidity. From a total of 520 prospective participants, 493 completed the survey, and the response rate was 92%. For further analysis, we excluded participants who had missing data for PA, demographics, health-related behaviors, and clinical health conditions. Therefore, a total of 481 participants were included in the study. All the participants received an explanation of the study protocol, and they provided their written informed consent to take part.

To assess the level of PA, we used the Korean version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). IPAQ is a self-reporting instrument used to assess the usual physical activities; it includes three domains that measure the frequency and duration of walking. These include moderate (e.g., easy walking) and vigorous (e.g., fast walking) activity for periods of at least 10 minutes during the past seven days. Walking and moderate physical activity were classified as <150 (low) and ≥150 minutes per week (high), and vigorous intensity PA was classified as <75 (low) and ≥75 minutes per week (high). We assessed time spent sitting during weekdays and categorized this into two groups: < 8 (low) and ≥8 hours per day (high). We also assessed the level of participation in sports activities as either ‘yes’ (those who participated in any sports activity at least once a week) or ‘no’ (never). We categorized participants as ‘inactive’ (not meeting the PA guidelines and never participating in sports), ‘sports activities’ (not meeting the PA guidelines but participating in sports), and ‘met PA guidelines’ (meeting the PA guidelines but not participating in sports).

Hypertension was assessed using a self-reported questionnaire. We indicated hypertension from a physician’s diagnosis or from the participants taking medicine to lower their blood pressure.

We considered confounding factors of age, sex, education level, household income, sedentary time and presence of diabetes. Education levels were categorized as ‘< high school,’ ‘high school,’ and ‘≥ college.’ Household income was categorized as ‘low,’ ‘middle,’ or ‘high’.

All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics version 24 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Participants’ characteristics were indicated as number (percentage) for categorical variables. Statistical significance of participants’ characteristics with regard to meeting PA guidelines or sports activities was calculated using chi-square tests. We also calculated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for hypertension according to PA status using multivariate logistic regression. Model 1 was adjusted for age and sex; model 2 was additionally adjusted for education levels and household income; model 3 was additionally adjusted for sedentary time and self-reported diabetes.

Table 1 lists the participants’ characteristics. Overall, 481 participants (251 males and 230 females) were included in the study. Among the participants, 65.7%, 36.0%, and 42.6% met the physical activities guidelines for walking, moderate, and vigorous activity, respectively. Overall, 52.8% met the PA guidelines, with the percentage equal to 28.3% among those with higher sedentary time. In addition, 47.2% participated in sports activities. Participants who met the PA guidelines tended to be males, younger, better educated, and have higher income levels (data not shown).

The participants’ characteristics with respect to participation in sports activities are presented in Table 2. Subjects participating in sports activities tended to be males, to be younger, and to have higher levels of education and income.

Table 3 presents the results concerning the association between meeting the PA guidelines and participating in sports activities and the risk of hypertension. We categorized subjects as inactive (not meeting the physical activities guidelines and not participating in sports), participating in sports but not meeting the guidelines, and meeting the PA guidelines. We observed a lower risk of hypertension in the sports activities group compared with inactive group after adjusting for age and sex (OR: 0.42, 95% CI: 0.17-0.99). In addition, these results were unchanged after adjustment for education levels and household income (Table 3, model 2). In the fully adjusted model, the ORs for hypertension were 0.36 (95% CI: 0.13-0.97) for the sports activity group and 0.33 (95% CI: 0.14-0.78) for those who met the PA guidelines (Table 3, model 3).

In the present study, we aimed to evaluate PA patterns according to participation in the sports for all programs in community-dwelling Korean adults. We also investigated the association between meeting the PA guidelines and participation in sports activities with the risk of hypertension. Our findings suggest that participation in sports activities is associated with higher rates of meeting the PA guidelines. However, the amount of daily sedentary time was not affected by participation in sports activities. In addition, we found that participation in sports without meeting the PA guidelines’ level was associated with a decreased risk of hypertension after adjustment for potential confounding factors.

Among the study subjects who participated in the sports for all program, hiking was the most common activity at 21.6%, followed by badminton (14.1%), and football (12.3%). There were 176 people who participated in sports for all but who did not meet the PA guidelines. Interestingly, there was no difference in the time spent in sedentary behavior between individuals who participated in sports for all and non-participants.

A growing body of evidence suggests that meeting PA guidelines contributes to a reduction in the risk of chronic disease and a decreased risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality [1,3,14,16,17].

This study suggests that participation in sports activities, even among those who have not met the PA level recommended by the current guidelines, is associated with reduced risk of hypertension. Leisure time has been the most widely investigated domain of PA regarding possible health benefits [7,14,18]. Leisure time activity is also the most commonly explored domain in the literature, and it has been consistently reported that PA is associated with better health. However, previous studies have not investigated whether activity levels less than 150 minutes per week are sufficient to decrease the risk of hypertension.

In this study, individuals who participated in sports but did not meet the PA guidelines had significant health benefits when compared to those with inactive lifestyles. Many previous studies have reported dose-response relationships between PA and measures of health. The findings from these studies suggest that even a modest amount of participation in PA or sports is beneficial to one’s health. Consistent with our findings, Wen et al. reported that a daily average of 15 minutes of exercise during leisure time was associated with a 10% reduction in all-cause mortality in a large Taiwanese population [19]. Moreover, a large prospective cohort study showed that individuals who were active during 1-2 sessions/week had reduced risks of all-cause, CVD, and cancer mortality than inactive individuals in a pooled analysis of 11 cohorts from the Health Survey for England and Scottish Health Survey [20]. Taken together, the results of our study and previous reports suggest that participation in PA, even at levels below the PA guidelines, helps reduce the risk of hypertension.

Regular PA stimulates the vascular endothelial cells to maintain blood vessel elasticity, and this protective effect may prevent hypertension. In addition, long-term follow-up studies show that leisure time PA contributes to the prevention of obesity, which affects the onset of hypertension. Participation in PA is related to reduced incidence of metabolic diseases including metabolic syndrome. In addition, increased PA levels have been associated with reduction of the systolic and diastolic blood pressure in participants with hypertension [13].

We may extrapolate from previous studies to explain why relatively low levels of PA have positive health benefits. Although the effect of PA on health outcomes has a dose-dependent relationship, the most significant effects on health result from the first hour of activity per week [1]. This curvilinear relationship between PA and health benefits has been reported in systematic reviews using meta-analysis [21-23]. Furthermore, in most previous studies, individuals who had less than 150 minutes per week of PA were categorized as inactive, and thus the analyses were unable to evaluate the effects of low-level PA on health outcomes. In Korea, participation in sports activities during the weekend is increasing due to a lack of leisure time during weekdays. The guidelines recommend that adults aged 18-64 years should perform at least 150 minutes of moderate activity per week, at least 75 minutes of vigorous intensity activity per week, or an equivalent combination. However, the frequency of activity is not specified by the guidelines. Recently, a study of ‘weekend warriors’ who performed all their PA during 1-2 sessions per week reported that participation in PA, even without meeting the PA guidelines, helped reduce the risk of all-cause, CVD, and cancer mortality [20]. Therefore, our study and previous studies suggest that individuals who wish to participate in PA but do not have enough time during the week can benefit from weekend sports. However, further studies concerning the risk of musculoskeletal injuries or cardiovascular events that may occur during high-intensity activity are needed.

The present study has several limitations. We used data from self-reported PA using the IPAQ. Measuring self-reported PA using a questionnaire can be biased toward overestimation. In addition, our subjects were volunteers who participated in the survey and were physically active. In fact, the participants in this study reported higher level of PA compared to that of the average Korean adult. Finally, because the design of our research was a cross-sectional study, we could not clarify causal relationships between sports activity and reduced risk of hypertension. Future research will require prospective studies using objectively measured PA.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Korea Ministry of Education (Grant No. 2014R1A1A2059106, 2017R1D1A1B03035192). The funders had no role in this study design, data collection and analysis and prepared all results.

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics

Table 2.

Participants’ characteristics with respect to participation in sports activities

Table 3.

Association between meeting the physical activity guidelines and participation in sports activities and the risk of hypertension

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

| Inactive (n=102) | 1.00 | (reference) | 1.00 | (reference) | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Sports activities (n=176)a | 0.42 | (0.17, 0.99) | 0.38 | (0.15, 0.97) | 0.36 | (0.13, 0.97) |

| Met guidelines (n=203) | 0.39 | (0.17, 0.88) | 0.38 | (0.17, 0.88) | 0.33 | (0.14, 0.78) |

References

1. Wen CP, Wai JP, Tsai MK, et al. Minimum amount of physical activity for reduced mortality and extended life expectancy: A prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2011; 378(9798): 1244–53.

2. Yoshizawa Y, Kim J, Kuno S. Effects of a lifestyle-based physical activity intervention on medical expenditure in japanese adults: A community-based retrospective study. BioMed Research International. 2016; 2016:6.

3. Kim J. Association between meeting physical activity guidelines and mortality in korean adults: An 8-year prospective study. J Exerc Nutrition Biochem. 2017; 21(2): 23–9.

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. 2008 physical activity guidelines for americans. 2008; http://health.gov/paguidelines/pdf/paguide.pdf.

5. The Ministry of Health and Welfare. The physical activity guide for koreans. 2013; http://health.mw.go.kr/ReferenceRoomArea/HealthFileRoom/healthFileDetail.do?ED_NO=1851(Accessed 31 Oct., 2016).

6. Kim J, Tanabe K, Yokoyama N, Zempo H, Kuno S. Association between physical activity and metabolic syndrome in middle-aged japanese: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2011; 11:624.

7. Samitz G, Egger M, Zwahlen M. Domains of physical activity and all-cause mortality: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2011; 40(5): 1382–400.

8. Yates T, Davies MJ, Gray LJ, et al. Levels of physical activity and relationship with markers of diabetes and cardiovascular disease risk in 5474 white european and south asian adults screened for type 2 diabetes. Prev Med. 2010; 51(3-4):290–4.

9. Waller K, Kaprio J, Lehtovirta M, Silventoinen K, Koskenvuo M, Kujala UM. Leisure-time physical activity and type 2 diabetes during a 28 year follow-up in twins. Diabetologia. 2010; 53(12): 2531–7.

10. Kim J. Longitudinal trend of prevalence of meeting physical activity guidelines among korean adults. Exerc Med. 2017; 1:2.

11. Marques A, Peralta M, Martins J, de Matos MG, Brownson RC. Cross-sectional and prospective relationship between physical activity and chronic diseases in european older adults. Int J Public Health. 2017; 62(4): 495–502.

12. Marques A, Peralta M, Sarmento H, Martins J, Gonzalez Valeiro M. Associations between vigorous physical activity and chronic diseases in older adults: A study in 13 european countries. Eur J Public Health; 2018.

13. Kim J, Tanabe K, Yoshizawa Y, Yokoyama N, Suga Y, Kuno S. Lifestyle-based physical activity intervention for one year improves metabolic syndrome in overweight male employees. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2013; 229(1): 11–7.

14. Liu Y, Shu XO, Wen W, et al. Association of leisure-time physical activity with total and cause-specific mortality: A pooled analysis of nearly a half million adults in the asia cohort consortium. Int J Epidemiol 2018.

15. Werneck AO, Oyeyemi AL, Gerage AM, et al. Does leisure-time physical activity attenuate or eliminate the positive association between obesity and high blood ressure? J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2018.

16. Lee IM, Rexrode KM, Cook NR, Manson JE, Buring JE. Physical activity and coronary heart disease in women: Is "no pain, no gain" passe? Jama. 2001; 285(11): 1447–54.

17. Bijnen FC, Caspersen CJ, Feskens EJ, Saris WH, Mosterd WL, Kromhout D. Physical activity and 10-year mortality from cardiovascular diseases and all causes: The zutphen elderly study. Arch Intern Med. 1998; 158(14): 1499–505.

18. O'Donovan G, Stamatakis E, Stensel DJ, Hamer M. The importance of vigorous-intensity leisure-time physical activity in reducing cardiovascular disease mortality risk in the obese. Mayo Clin Proc 2018.

19. Wen CP, Wai JPM, Tsai MK, et al. Minimum amount of physical activity for reduced mortality and extended life expectancy: A prospective cohort study. The Lancet. 2011; 378(9798): 1244–53.

20. O'Donovan G, Lee IM, Hamer M, Stamatakis E. Association of "weekend warrior" and other leisure time physical activity patterns with risks for all-cause, cardiovascular disease, and cancer mortality. JAMA Intern Med. 2017; 177(3): 335–42.

21. Physical activity guidelines for americans: Appendix 1. 2008; 30(3): 213–24. https://health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/appendix1.aspx).